With the constant barrage of high-pressure advertizing forced on us as we try to go about our everyday lives, we occasionally wistfully think of days gone by, when times were more relaxed and simpler. Nowadays, we poor consumers need to be protected by ever more complex laws to shield us from decepetive and misleading advertizing, and even downright fraud. Despite potential fines of millions of dollars, companies try every trick in the book to part us from our hard-earned cash. Oh for those good old days!

Maybe it seems this is something relatively new, a phenomenon born of the 1980's and 90's, but the reality is that the advertizers and marketers have been using techniques of manipulation and deception for a long, long time. What's more - and what is perhaps really shocking to us Watch Enthusiasts and Collectors - is that the Watch Manufacturing industry, whom we collectors tend to hold in the highest esteem, have been using all the same strategies as everyone else to get that all-important sale.

While there are a number of ways they continue to do this, here we will focus on an area which has probably been, certainly until the advent of the cheap quartz watch at least, the single most important factor in indicating the quality of a timepiece - the number of jewels a watch has.

Before we proceed further, let's recap on what jewels in watches are, and what purpose they serve. Long ago in the early days of watch and clock making, it was realized that friction in the moving parts of a clock or watch, in particular the escapement, had a major effect on timekeeping accuracy. It was found that the harder the material was that the bearings were made of, the lesser was the friction of the bearing, enabling better control of timekeeping and as a bonus, the life of the bearing was considerably extended. The hardest known materials at the time which could be cut were sapphires and rubies. The stones used were naturally-occuring and were hand cut on lathes using diamond powder as the cutting agent, into little flat cylinders with a very fine hole drilled in them. Actually, sapphires and rubies (which are simply aluminum oxide in large crystalline form, otherwise known as corundum) are second in hardness only to diamond, the hardest substance know to man. The only difference between a sapphire and a ruby is the color, which is determined by small impurities.

|

Suitable stones for watch jewels had to be obtained by mining natural mineral deposits. Watches generally only had jewels used where it did the most good, usually in the escapement where friction has a major effect. In a lever watch, a fully-jewelled escapement would contain seven jewels - two each for the upper and lower balance pivots, one for the impulse roller, and the remaining two for the pallets. Only watches of exceptional quality and value would have more. Jewels would generally be set in little brass or gold carriers, known as chatons, which were mounted into the watch plates with small screws, a very labor intensive operation requiring great skill. The example you see here is an English watch of around 12 size, which has eleven sapphire jewels, made in 1877. Perhaps you can see now that jewels in watches once had a real monetary value and significance, related not only to their function, but also due to their origin, rarity and the technical difficulties in working with them. |

In 1902, a method was developed for artificially creating synthetic rubies and sapphires (click here for details). Now the watch industry had a source of stones that not only was cheap and plentiful, but was of a far higher purity and without the mechanical flaws found in naturally-occurring stones.

So, here we have any marketing department's dream come true! A highly valued commodity, suddenly being able to be manufactured for only a fraction of the price it used to be. Shall we pass the savings on to the customer? Of course not! And thus the myth of watch jewels was - well not exactly born - but "nurtured" to the benefit of the watch companies.

In October 1965, the Swiss organization NIHS (NIHS Normes de l'industrie Horlog re Suisse), whose function is to develop standards for the Swiss watch industry, published a standard (NIHS 94-10) in an effort to control the manner in which jewels may be referred to in advertising and sales literature of horological and timekeeping instruments. In 1974, NIHS in conjunction with the International Standards Organization (ISO) published the standard ISO 1112, which has been recently updated (1999). The standard mentions that the jewels would usually be ruby. Incidentally, stones of many kinds have been used as watch jewels, including ruby, sapphire, garnet, diamond, and yes, even glass. So you may well ask "what about the period between 1902 and 1965 when there were no official standard". Well, it was "anything goes" when it came to the jewelling of watches, with all kinds of methods used to increase the jewel count of a watch, many of which served no useful purpose. Often, jewels were added in such a way as to make it look like they were useful, but to a watchmaker who looked a little closer, the truth was plain to see.

The ISO standard is written to clearly establish what can be termed a functional or non-functional jewel. It defines a functional jewel as a "jewel which serves to stabilize friction and to reduce the wear rate of contacting surfaces of the components of a timekeeping instrument". It defines a non functional jewel as a "jewel used for purposes other than as defined in 3.2" (ie a Functional Jewel). In addition, the standard contains detailed drawings which clearly define the functionality of various combinations of jewels and pivots. I would like to propose a third category - which I will call "Useless Jewels". That is, jewels which are technically functional according to the ISO standard, but which are used in places which serve no effective purpose other than to increase the jewel count of a watch. We will look at some examples of these later.

|

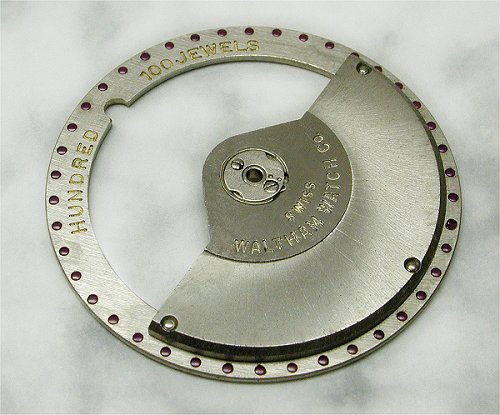

The automatic watch movement shown here would very likely be the Grandaddy of all watches when it comes to non-functional jewels. It is the Waltham 100 Jewel watch movement, and takes pride of place along with it's cousin, the Waltham 75 Jewel watch movement as being among the movements with the highest number of non-functional jewels ever made. Looking at this movement now, it is hard to imagine if the Waltham Company was seriously trying to market this watch as being better due to the high jewel count, or whether it was just a huge gag - that ended up being taken seriously. Unfortunately, I don't have any of the advertizing material on these watches to get a sense what their ideas were. Neverthless, history remembers it as a 100 jewel watch. |

|

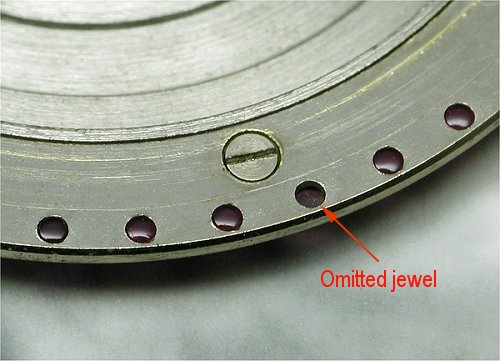

The edge of the automatic rotor, shown here, is studded with small flat ruby jewels on both sides. There are 83 jewels fitted in the possible 84 locations, and adding them to the 17 jewels of the movement makes a total of 100. Two polished rings, assembled around the rotor, allow clearance for the rotor to move freely, but should the watch receive a shock, the rotor will displace and the jewels will (theoretically at least) rub on the inside of the rings. |

|

Here an unused space can be seen, the jewel being deliberately omitted to bring the total number of jewels to exactly 100, a nice round number for the marketing department to deal with! |

|

The polished inner races of the rings can be seen. There is no evidence on this movement that the rotor jewels have ever actually come into contact with these rings. However, wear marks can be clearly seen on the rotor and movement, where the rotor has contacted the pillar plate of the watch during a shock, the same as you would see on a normal automatic movement. |

|

Underneath the rotor is the reality behind the facade...a plain 17 jewel Eta 1700 - a humble, yet good quality workhorse, fitted with a glucydur balance making it quite capable of excellent timekeeping. Not exactly the glittering 100 jewel spectacle one might have been expecting! |

At first glance, it appears that indeed the 83 extra jewels are serving a useful function. But, they do not significantly add anything at all to the functionality of the watch, either in its timekeeping ability, or the efficiency of the automatic winding mechanism, or for that matter, the life expectancy of the movement. In fact, the ISO 1112 standard specifically states that stones added to automatic winding weights, in the manner as the example above, cannot be termed functional jewels. Though I can't say for sure, I suspect that it is this very movement and its 75 jewel cousin which prompted such a specific exclusion in the official standard.

|

This 19 ligne (around 16 size) Swiss Fleurier movement from the 1930's is really only a low-grade 15 jewel movement. Not low grade due to it only having 15 jewels, but simply due to the low standard of construction and finish. It has been "beefed up" to 21 jewel status by the crudely executed addition of cap jewels. These cap jewels, which in fact are not rubies or sapphires but garnets, do not contact any moving parts. Hence they are non-functional. I believe this movement (and the one below), and others similar, were Swiss "fake" Railroad watches, trying to steal a share of the Railroad Grade pocket watch market. |

|

This is a close-up shot of the top escape pivot of the Fleurier movement above, with the cap jewel removed. Note that the top pivot is well below the level of the top surface of the cock in which it is mounted. It could never reach the cap jewel and make it functional. |

|

Here is another example of non-functional cap jewels applied to a low grade watch to artificially increase its jewel count to 21 jewels. This is a Swiss 19 ligne pocketwatch movement from a similar era to the Fleurier movement above. Once again, cheap garnets were used as the cap stones. Here, the relatively soft garnet endstone on the center wheel has a hole punched through it (same as the Fleurier movement above), from excessive end play of the center wheel when the hands have been pressed on at some time. Capping a center wheel would have to be one of the most totally pointless watchmaking exercises, serving no purpose except to increase the jewel count. |